The Easy Way To Domain Adaptation

In the deep learning era it seems that once you have sufficient labeled data, you can train a model to solve almost every problem. However, collecting suffic...

In the deep learning era it seems that once you have sufficient labeled data, you can train a model to solve almost every problem. However, collecting sufficient labeled data is not an easy task. In real-world problems, the data rarely looks like the data you can find in official datasets. Consequently, researchers explore diverse avenues to circumvent the scarcity of labeled data, from simulations to zero-shot learning. In this post, I would like to share my experience in tackling the problem of lacking label data using unsupervised domain adaptation (UDA).

During my Ph.D., I extensively explored domain adaptation (DA) methodologies across various contexts. While some of these methods can be quite intricate, the pragmatism of real-world problems often calls for simpler solutions. In many cases, a simple solution can be faster, cheaper, and even more robust. Drawing from my roles as both a CTO and Chief Data Scientist, I’ve guided numerous research teams in implementing UDA for real-world challenges. Frequently, data scientists are tempted to adopt the latest state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods without considering implementation costs. I found myself again and again drawing a path that explains what they should try first, and what they should try only if there is no other choice. I will now share this path with you, but first, let’s explain what UDA is.

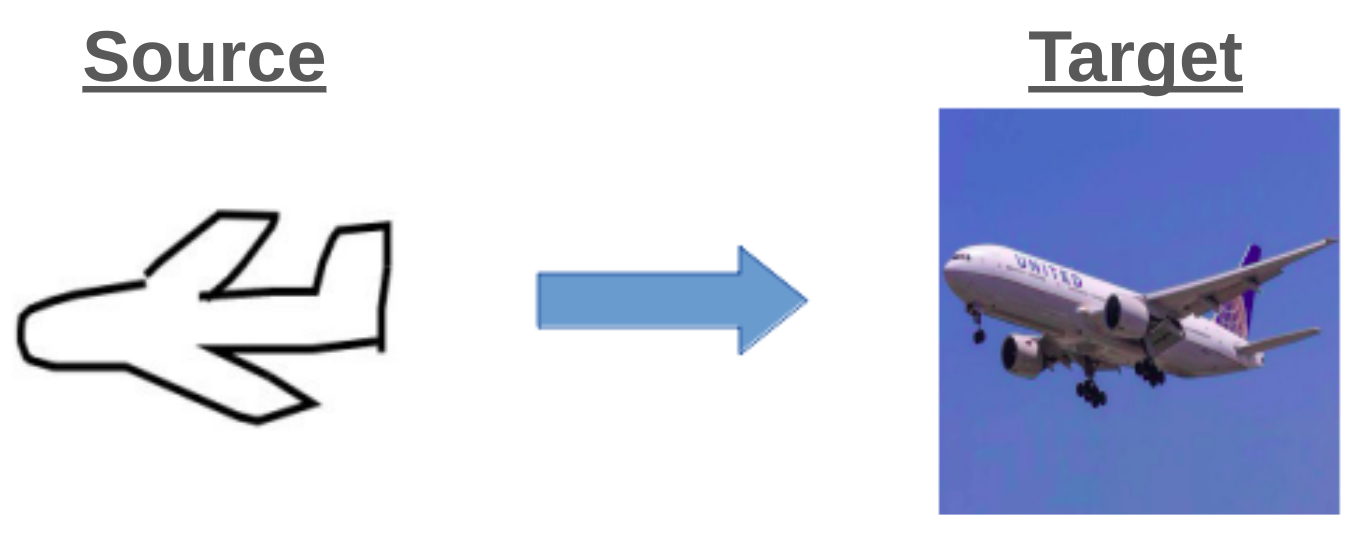

In unsupervised domain adaptation, labeled samples are given from a source domain and we wish to make predictions on a target domain, from which only unlabeled samples are available. For example, images may be taken under several lighting conditions, medical data may be collected using different versions of a sensor, and product reviews may be collected for different products. In all of these cases, we may have labeled data from one type, but can not invest the effort to actively label all different types. The data type we have labels for is called the source domain, and the type without the labels is called the target domain.

So, you have label data from your source domain, and now you want to create a model for your target domain. What should you do?

Often, acquiring some labeled data from your target domain is feasible, even a small subset might suffice. If this can be accomplished at a low cost, it’s advisable to attempt this approach initially.

This approach doesn’t always guarantee success, but it takes 30 seconds to implement, and from my experience sometimes reduces the domain gap by up to 80%(!), making it worth a try in all cases.

The main idea is to adapt the normalization of the data to the target distribution. There are many ways to do that, but Li et. al. suggest a very convenient implementation.

A common training process should look like that:

#Train model

model.train()

for i in range(train_epochs):

for X,y in train_dataloader:

pred = model(X)

…

Then you test the model on the target domain: (Note that if you really don’t have any labels this is not a trivial question about how to evaluate your model on the target. I may write about that in another post)

#Test model

model.eval()

for X,y in test_dataloader:

pred = model(X)

…

Now, all you should do is add those 3 lines, after the training:

model.train()

for X,y in target_dataloader:

_= model(X)

How does this help? Utilizing model.train() ensures that the model continues updating the running_mean and running_var in the batch normalization layer. Iterating once on the target data allows the normalization to adapt to the target distribution, potentially improving performance.

We wish to learn from the source labels information and then apply it to the target. It is natural to emphasize source samples similar to the target domain. But how can we know how to decide on the weight of each sample? We can learn it! Since we have access to both source and target data, we can train a binary classifier (denoted as f) to predict if a sample is from the source domain or the target domain. Assuming that: f(x in S)=0 and f(x in T)=1, we modified the training cross-entropy loss to p(x)f(x)log(q(x)). This way we give higher weight to source samples more similar to the target.

criterion = nn.CrossEntropyLoss(reduction='none')

output = model(x)

samples_weight = f(x)

loss = criterion(output, y)

loss = loss * samples_weight

loss.mean().backward()

It’s worth noting that if the source and target domains are vastly different, a proficient classifier will perfectly separate them and assign a weight of 0 to all source samples. To mitigate this issue, you can employ a less expressive model, introduce regularization, or employ early stopping techniques.

This method operates without requiring the presence of target data during training. Wand et. al. suggests a simple yet effective approach for this setup. The training process remains unchanged. However, during inference when encountering target data, we adapt the model’s weights to minimize the entropy of predictions on the current batch. This strategy yields promising results, particularly when the domain gap is not substantial, such as with small perturbations. The “know-how” of this method is to update only the normalization layers of the models, which includes normalization statistics and affine parameters. This way the update is more stable and efficient.

If you’ve reached this stage and none of the previous methods yield satisfactory results, congratulations! You’re encountering a non-trivial problem. However, fret not! There are still numerous other solutions to explore 🙂. In the following sections, I’ll concentrate on the core concept of each cluster of methods. Keep in mind that each method discussed here may have numerous variants and additional details that can enhance its effectiveness beyond the vanilla version I explain here.

The main idea of SSL is to learn a good representation of the data without any labels. This is a very useful method, but it falls outside the scope of this post and thus won’t be covered here. If you do not know anything about SSL, I recommend you take some time and learn it in depth (for example from here and here). However, in the context of Domain Adaptation (DA), SSL can be employed to compel the model to utilize a feature space that effectively represents the target domain. There are two primary approaches to using SSL for domain adaptation:

A prevalent approach in domain adaptation research is the implementation of an adversarial loss. The premise is straightforward: enforce the source and target domains to utilize a shared embedding space, and train a classifier to classify the source domain within that space. The assumption is that if the source and target domains align adequately, the classifier will generalize well to the target domain.

This idea stems from the seminal work of Ganin et al., which was one of the pioneering applications of domain adaptation in deep learning. Given its elegance and simplicity, many researchers often attempt this approach first, hoping for straightforward success. However, in practice, training with adversarial loss can be unstable and challenging. It typically requires significant effort in parameter tuning and meticulous fine-tuning to achieve satisfactory results.

While this approach can yield impressive outcomes after considerable investment and careful adjustment, I advocate against adopting it as the initial strategy. Instead, it’s best reserved for later stages of exploration.

This method addresses a common drawback of techniques aiming to map both the source and target domains to a shared representation. Often, this sharing of representations leads to “negative transfer,” where features beneficial for the source domain overshadow those crucial for the target domain, thereby impairing inference on target data.

To mitigate this issue, one strategy is to train a model without exposure to any source features. This is achieved by training a model on the source domain (referred to as the “Teacher”) and using it to predict labels on the target domain. Subsequently, another model (referred to as the “Student”) is trained using the target data alongside the pseudo-labels predicted by the teacher. Consequently, the student network avoids overemphasizing source features at the expense of those essential for the target domain.

In my research, I demonstrated that if the student network is employed to predict labels for the source domain, this information can aid the teacher network in refining its pseudo-labels for the student network.

We begin this post with a method advocating the use of target samples instead of domain adaptation. A fitting conclusion is to end with a DA method that essentially achieves a similar goal. This method involves training a generative model using both the source and target data to perform style transfer from the source domain to the target domain, while preserving the labels of the samples. With this model in hand, we can apply it to all our source domain samples, generating a dataset of target-like samples with corresponding labels. Subsequently, we can train a model using this augmented dataset.

While these methods are highly effective, it’s worth noting that training generative models can be challenging. Hence, this approach is typically reserved as a last resort.

I hope this post will be useful for you. Please let me know how those suggestions work in your problem! If you have any other tips for practical UDA I will be very happy to hear them.

In the deep learning era it seems that once you have sufficient labeled data, you can train a model to solve almost every problem. However, collecting suffic...